As I prepare to leave next week for the D.C. Pen Show, packing the Delta Dolphin fountain pens has reminded me just how large an influence our oceanic cousins have played in my thoughts over the course of my life. I don't stock many Delta pens as a rule, but when the latest addition to their Animals series was announced (joining the Crocodile, Elephant and Polar Bear), I just couldn't help myself.

Delta Dolphin pen

Dolphins captured my attention early on, primarily due to the research of Dr. John Lilly in the 1950's, who wrote a number of fascinating books on the subject of dolphin intelligence and interspecies communication (he largely worked with Tursiops Truncatus, the Bottle-nosed dolphin, familiar to many as the star of the Flipper TV series in the 60's). Although superseded by other researchers and more recent work, there's still great value in returning to some of those original reports that grew out of Lilly's work for the U.S. Navy, in books such as Communication Between Man and Dolphin.

Growing up, I voraciously read anything I could lay claim to on the subject of Cetaceans (dolphins, porpoises and whales) and would watch aquarium dolphin 'shows' -- whether live or on TV -- whenever possible. Several dolphin "trainers" (something of a misnomer, as often it's the dolphin that seems to be training the human) suggested that I might want to pursue that occupation, but by then I couldn't see myself working with captured dolphins. Lilly progressed from initially 'sacrificing' (the polite term used in medicine and biology to replace 'killing') dolphins in order to autopsy them and examine their brain structure in detail, to later refusing to continue his work until a facility could be constructed where the dolphins were free to come and go as they chose (he found that several were as interested in pursuing the cognitive studies as he was!).

Lilly came to believe that the bottle-nosed dolphin was at least as intelligent as homo sapiens - having a 30% larger brain, with a neocortex as complex as our own, routinely processing about 2-1/2 times the amount of sensory information per second that we do (more often acoustical than visual, due to their amazing echo-location) and solving intricate social and cognitive challenges - often more quickly than the human participants. It's quite telling that the attempts at interspecies communication through language acquisition have been most successful when it's the dolphin learning our language. Many of Lilly's seemingly outrageous claims -- such as that the most advanced minds on the planet belong to whales (the sperm whale has a brain of apparently equal complexity to our own, as measured by neuronal density and depth of neocortical creases or convolutions -- but is 6 times larger) -- leave many marine biologists amused at best. However there is also a growing body of evidence from other researchers that appears to corroborate many of his suppositions and anecdotal accounts.

I'll leave Lilly's later researches into human consciousness through psychotropic drugs and sensory deprivation -- with himself as the test subject -- for another time, but books such as The Center of the Cyclone and Programming and Metaprogramming in the Human Biocomputer make for equally engrossing reading.

In the mid-80's I finally had the opportunity to have a close encounter of the dolphin kind, for myself. Although I'm not sure that it's still in existence, at that time there was a marine mammal rescue and research center in West Dennis, on Cape Cod, MA, which I had discovered on one of my trips to the Cape to visit my friend Joannie, who lived in nearby Chatham. They had a program at that time, in order to raise funds for research and rescue, that consisted of a two-hour lecture on Cetacean biology, followed by a swim with a rescued bottle-nosed dolphin named Scotty (I'm sure that must have been the name he gave them).

This was a number of years prior to the widespread 'swims' adopted by Seaquariums, employing their captive, performing dolphins. As Scotty was a rescued animal, being nursed back to health for eventual release 'home', the large tank that was his temporary abode was fed fresh seawater directly from the bay for his comfort -- not ours. Consequently, any humans entering the tank for a tete-a-tete with Scotty were exposed to the chill Cape Cod water, necessitating the use of a wetsuit.

My first experience in a wetsuit was an experience. Just getting into one of these things takes time, strength, patience and copious amounts of baby powder. Once in the water, I quickly learned that these things are buoyant -- from neck to ankle. If you want to just wade in the water, legs down doesn't do it (that tends to flip you on your back). You have to actually assume a sitting position underwater in order to maintain an upright posture with your head out.

But I'm getting slightly ahead of myself, for actually getting into the water with Scotty produced a moment's trepidation. Here was a wild animal, weighing in at about 450 lbs., in his environment, and as far as I knew my invitation to join the swimming party hadn't been cleared with him. If he decided that I wasn't welcome, it would have been nothing for him to have flipped me out (pun intended), despite my not inconsiderable bulk. Or, raking me with his exceedingly sharp teeth would have also spoiled my day (dolphins routinely kill sharks in the wild, usually by ramming their gills at high speed with their 'beak' and lower jaw).

Yet, all that I knew intellectually about the species quickly allayed those fears. The recorded history of man/dolphin interaction, going back thousands of years and continuing today, almost unfailingly demonstrate the dolphin's keen interest in, and benevolence toward, his two-legged cousin. The anecdotes and documented cases of wild dolphins coming to the aid of shipwrecked sailors and people near to drowning, are legion. It's as if they can directly sense a kindred intellect and spirit, and go out of their way to protect us (driving off sharks, as an example). And those senses are acute.

Within seconds of entering the large tank, even before I had seen the submerged dolphin, Scotty made his presence known to me -- as I felt a tingling sensation traverse my body -- head-to-toe. That tingling was produced by Scotty directing his 'sonar', or more properly 'echo-location clicks' which not only told him my precise location, but also informed him of my respiration, heart-rate and other bodily functions -- which quite probably gave him a fair idea of my emotional state. Dolphins are highly social beings, and apparently rely a great deal on these non-verbal signals to gauge the status of another's emotions, much as we rely upon similar visual clues. However, Scotty knew a lot more about me in those first few seconds than I could discern about him.

He also subsequently showed great interest in my shorter right leg (a result of a childhood automobile accident and corrective surgeries), by the prolonged attention he exhibited to that area of my anatomy, both with directed echo-location and close visual inspection. Dolphins have a penchant for being most attentive in human/dolphin interactions to those individuals who seem 'different' or injured, and whole swim programs have been developed around the extreme gentleness and approachability they exhibit toward physically, emotionally or mentally challenged children and adults.

As the swim progressed (I had snorkle gear, which allowed me to peer at Scotty underwater as well) I removed one of my neoprene gloves to stroke Scotty on one of his passes. The closest approximation I've been able to come to in describing the feeling of his skin and body underneath my fingertips was that of a 450 lb. hard-boiled egg (minus the shell, thank you). But the real highlight of the experience for me was to stare eye-to-eye with him. After all my years of reading and study concerning the nature of cetacean intelligence, I had no intellectual doubts about its high order. It wasn't until I looked into Scotty's eye, and he looked back however, that I knew I was sharing a basic level of communication with another intelligent being, quite possibly one that functioned in a mental world not too unlike the one that I and my fellow humans inhabit. I felt profoundly grateful for that moment of silent communion -- as well as the forebearance he showed during my early flailing around in his 'home' as I got used to the bouyant wetsuit (I was later told that I'd actually kicked Scotty in the head during my aquatic struggles!). Our search for extraterrestrial intelligence continues, but I am satisfied that we know of at least one other intelligence in the Cosmos on a rough par with our own, and taking into account the great whales, perhaps greater than our own -- but that's another story.

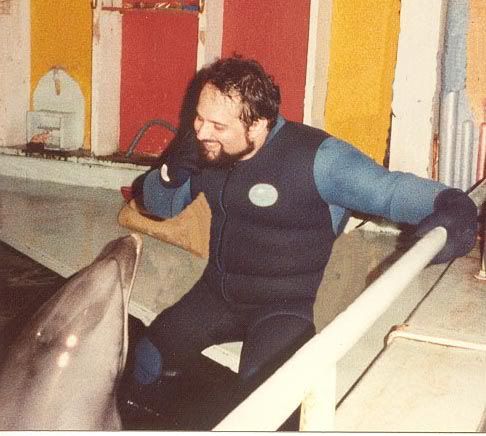

The photo below was one of a series taken immediately after my swim, as Scotty emerged from the tank to plant a farewell kiss on my cheek.

Growing up, I voraciously read anything I could lay claim to on the subject of Cetaceans (dolphins, porpoises and whales) and would watch aquarium dolphin 'shows' -- whether live or on TV -- whenever possible. Several dolphin "trainers" (something of a misnomer, as often it's the dolphin that seems to be training the human) suggested that I might want to pursue that occupation, but by then I couldn't see myself working with captured dolphins. Lilly progressed from initially 'sacrificing' (the polite term used in medicine and biology to replace 'killing') dolphins in order to autopsy them and examine their brain structure in detail, to later refusing to continue his work until a facility could be constructed where the dolphins were free to come and go as they chose (he found that several were as interested in pursuing the cognitive studies as he was!).

Lilly came to believe that the bottle-nosed dolphin was at least as intelligent as homo sapiens - having a 30% larger brain, with a neocortex as complex as our own, routinely processing about 2-1/2 times the amount of sensory information per second that we do (more often acoustical than visual, due to their amazing echo-location) and solving intricate social and cognitive challenges - often more quickly than the human participants. It's quite telling that the attempts at interspecies communication through language acquisition have been most successful when it's the dolphin learning our language. Many of Lilly's seemingly outrageous claims -- such as that the most advanced minds on the planet belong to whales (the sperm whale has a brain of apparently equal complexity to our own, as measured by neuronal density and depth of neocortical creases or convolutions -- but is 6 times larger) -- leave many marine biologists amused at best. However there is also a growing body of evidence from other researchers that appears to corroborate many of his suppositions and anecdotal accounts.

I'll leave Lilly's later researches into human consciousness through psychotropic drugs and sensory deprivation -- with himself as the test subject -- for another time, but books such as The Center of the Cyclone and Programming and Metaprogramming in the Human Biocomputer make for equally engrossing reading.

In the mid-80's I finally had the opportunity to have a close encounter of the dolphin kind, for myself. Although I'm not sure that it's still in existence, at that time there was a marine mammal rescue and research center in West Dennis, on Cape Cod, MA, which I had discovered on one of my trips to the Cape to visit my friend Joannie, who lived in nearby Chatham. They had a program at that time, in order to raise funds for research and rescue, that consisted of a two-hour lecture on Cetacean biology, followed by a swim with a rescued bottle-nosed dolphin named Scotty (I'm sure that must have been the name he gave them).

This was a number of years prior to the widespread 'swims' adopted by Seaquariums, employing their captive, performing dolphins. As Scotty was a rescued animal, being nursed back to health for eventual release 'home', the large tank that was his temporary abode was fed fresh seawater directly from the bay for his comfort -- not ours. Consequently, any humans entering the tank for a tete-a-tete with Scotty were exposed to the chill Cape Cod water, necessitating the use of a wetsuit.

My first experience in a wetsuit was an experience. Just getting into one of these things takes time, strength, patience and copious amounts of baby powder. Once in the water, I quickly learned that these things are buoyant -- from neck to ankle. If you want to just wade in the water, legs down doesn't do it (that tends to flip you on your back). You have to actually assume a sitting position underwater in order to maintain an upright posture with your head out.

But I'm getting slightly ahead of myself, for actually getting into the water with Scotty produced a moment's trepidation. Here was a wild animal, weighing in at about 450 lbs., in his environment, and as far as I knew my invitation to join the swimming party hadn't been cleared with him. If he decided that I wasn't welcome, it would have been nothing for him to have flipped me out (pun intended), despite my not inconsiderable bulk. Or, raking me with his exceedingly sharp teeth would have also spoiled my day (dolphins routinely kill sharks in the wild, usually by ramming their gills at high speed with their 'beak' and lower jaw).

Yet, all that I knew intellectually about the species quickly allayed those fears. The recorded history of man/dolphin interaction, going back thousands of years and continuing today, almost unfailingly demonstrate the dolphin's keen interest in, and benevolence toward, his two-legged cousin. The anecdotes and documented cases of wild dolphins coming to the aid of shipwrecked sailors and people near to drowning, are legion. It's as if they can directly sense a kindred intellect and spirit, and go out of their way to protect us (driving off sharks, as an example). And those senses are acute.

Within seconds of entering the large tank, even before I had seen the submerged dolphin, Scotty made his presence known to me -- as I felt a tingling sensation traverse my body -- head-to-toe. That tingling was produced by Scotty directing his 'sonar', or more properly 'echo-location clicks' which not only told him my precise location, but also informed him of my respiration, heart-rate and other bodily functions -- which quite probably gave him a fair idea of my emotional state. Dolphins are highly social beings, and apparently rely a great deal on these non-verbal signals to gauge the status of another's emotions, much as we rely upon similar visual clues. However, Scotty knew a lot more about me in those first few seconds than I could discern about him.

He also subsequently showed great interest in my shorter right leg (a result of a childhood automobile accident and corrective surgeries), by the prolonged attention he exhibited to that area of my anatomy, both with directed echo-location and close visual inspection. Dolphins have a penchant for being most attentive in human/dolphin interactions to those individuals who seem 'different' or injured, and whole swim programs have been developed around the extreme gentleness and approachability they exhibit toward physically, emotionally or mentally challenged children and adults.

As the swim progressed (I had snorkle gear, which allowed me to peer at Scotty underwater as well) I removed one of my neoprene gloves to stroke Scotty on one of his passes. The closest approximation I've been able to come to in describing the feeling of his skin and body underneath my fingertips was that of a 450 lb. hard-boiled egg (minus the shell, thank you). But the real highlight of the experience for me was to stare eye-to-eye with him. After all my years of reading and study concerning the nature of cetacean intelligence, I had no intellectual doubts about its high order. It wasn't until I looked into Scotty's eye, and he looked back however, that I knew I was sharing a basic level of communication with another intelligent being, quite possibly one that functioned in a mental world not too unlike the one that I and my fellow humans inhabit. I felt profoundly grateful for that moment of silent communion -- as well as the forebearance he showed during my early flailing around in his 'home' as I got used to the bouyant wetsuit (I was later told that I'd actually kicked Scotty in the head during my aquatic struggles!). Our search for extraterrestrial intelligence continues, but I am satisfied that we know of at least one other intelligence in the Cosmos on a rough par with our own, and taking into account the great whales, perhaps greater than our own -- but that's another story.

The photo below was one of a series taken immediately after my swim, as Scotty emerged from the tank to plant a farewell kiss on my cheek.

Norman,

ReplyDeleteWonderful article. Your expression in the photo. at the end is poignant.

From your "pen friend"

Roy Walton, Scotland

Thanks for the story, Norm. Reminds me of my own encounter, and I agree with both you and Prof. Lilly (I already have one of his books).

ReplyDeleteit is so interesting

ReplyDelete